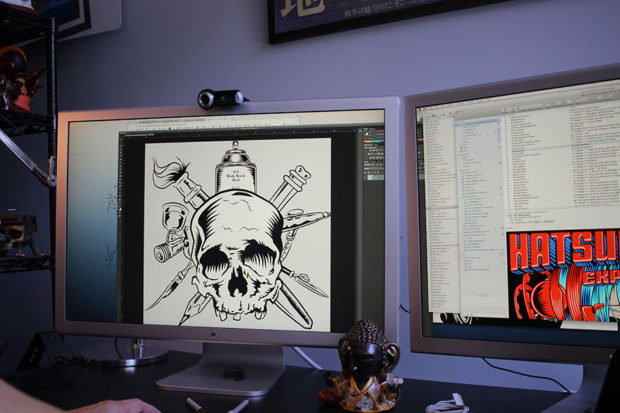

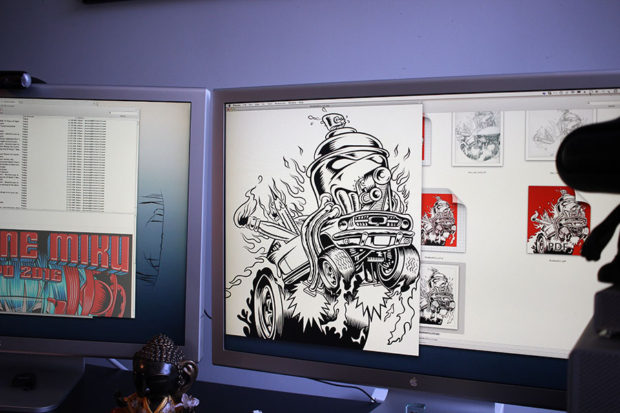

Jim Evans sits at a desk in his glass-walled studio in Malibu, casually clicking through a few projects he's currently working on. His latest client - a Japanese hologram named Hatsune Miku, who is leading the pop charts in Japan - sought out Evans, aka TAZ, to create a poster for the music sensation's upcoming tour. Evans rarely goes looking for work. After having created some of the most seminal music and film posters, album covers, and magazine illustrations, everyone from the Beastie Boys and Wu Tang Clan to the Ramones, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Rage Against the Machine have enlisted his artistic vision and edgy design over the years.

Jim Evans sits at a desk in his glass-walled studio in Malibu, casually clicking through a few projects he's currently working on. His latest client - a Japanese hologram named Hatsune Miku, who is leading the pop charts in Japan - sought out Evans, aka TAZ, to create a poster for the music sensation's upcoming tour. Evans rarely goes looking for work. After having created some of the most seminal music and film posters, album covers, and magazine illustrations, everyone from the Beastie Boys and Wu Tang Clan to the Ramones, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Rage Against the Machine have enlisted his artistic vision and edgy design over the years.

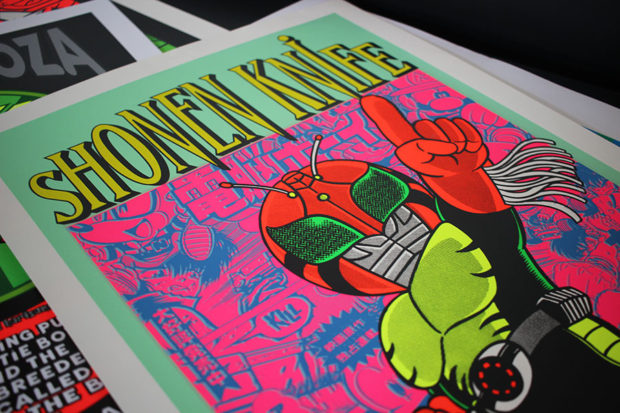

With something like 10,000 pieces of artwork in his catalog, Evans and his TAZ collaborations (which include his son Gibran, and long-time collaborator Rolo) are responsible for hundreds of gig posters and rock ephemera that have proven time and time again to act as time stamps of memorable music moments and important pieces of art and cultural history.

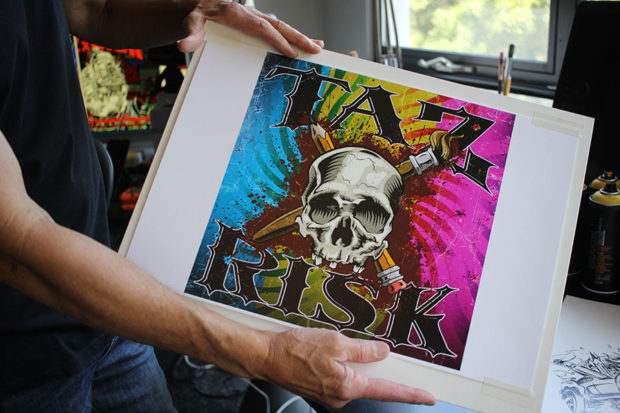

On Saturday May 14th, Buckshot Gallery will present a collaborative exhibition between acclaimed artist and printmaker TAZ and graffiti icon RISK, showcasing a selection of collaborative posters, originals and other genre related printed ephemera, created exclusively for the show, “Unconventional Forces".

We caught up with Jim Evans in the weeks leading up to the show at his Malibu home, where he told us about his early years creating comics for the psychedelic underground scene in San Francisco, what makes a great rock poster, and the evolution of TAZ.

Tell me about the social and musical climate in San Diego when you were growing up there.

It was the early sixties and all I did was surf. San Diego wasn’t the happening spot at the time; LA was definitely the place to be. There really wasn’t a cool music scene at all. So I started a surf rock band with some guys in high school, which morphed into a rock band pretty quickly. We had an interesting thing at the time, you know the whole English pop invasion thing was happening and washing away all American music. So we got onto that music pretty quickly and would drive to LA to buy new records by the Who and the Rolling Stones.

Would those bands stop for shows in San Diego?

Yeah I saw the Rolling Stones in San Diego in 1964 on their first American tour. They couldn’t even fill the auditorium; it was only about half-full. At that time the girls would just scream at all the bands. There weren’t many guys in the audience. It was pretty cool seeing them at the beginning. I saw Bob Dylan there, and I saw the Beatles at the baseball park in SD.

So you got your start playing in bands, when did you start making visual art?

I was always drawing as a kid, but by the time I was in 6th grade, I would get these hotrod magazines and then redraw these awesome cars on t-shirts and sweatshirts and sell them to my friends. They’d give me a shirt and twenty-five cents and then I would draw it for them. I never thought of myself as an artist, but I was always inspired by art, and would read about artists. And as the band started playing more and more, we needed posters, and drumheads, sometimes people would want their guitars decorated, and I was the guy doing all of it. So when other bands would see me drawing and designing posters for my band they would ask if I could do them for their band as well. I sort of became the guy who does the posters. I set up a little silkscreen in my bedroom and started making tons of posters.

As the 60s really started to blow up, people started to go up to San Francisco and visit Haight Ashbury. A friend of mine went up there and brought back these little posters that were more like postcards, and was like, ‘Hey this is pretty cool, you should check this out,” and when I saw the first San Francisco dance poster, I was like, ‘Holy shit!’ It was something that I had never seen before. It was like a light going off in my head. Like they were speaking in a secret code with their imagery, and I knew the code. So from there I started to put more into my posters and make them a little more psychedelic. There was LSD at the time that kind of lit up your mind too. I’d say in about 1967, I went up to Monterey Pop Festival and Haight Ashbury for a while and drove to Big Sur, and in a two–week span I went from Jimmy the little guy doing sketches, to like this illuminated mind. I felt like I had seen so much stuff in that two-week period of time that going back to Oceanside was like going back to an indigenous tribe. Seeing all the people and how they dressed in San Francisco, and around that city, my mind was blown. It seemed like a fully formed reality that I could just climb right into. I started to get really psychedelic – add a lot more color – with my drawings and put more of my philosophies into my work.

The Vietnam War was going on too, and I went into the service, in the Reserves, and I started working for a magazine, which I was shooting a lot of photos for at the time. I shot a lot of documentary style photos of the Black Panthers and the college riots. I had long hair so I was like the “house hippie”, and whenever some shit would go down they would always send me out to shoot it.

And all during this time you were still drawing and illustrating as well?

Yeah, actually I was sitting at a café in Westwood during this time, just sketching and drawing, and this guy Ron Cobb – he was pretty famous at the time, doing a lot of underground comics – he saw me sketching and he said he had a friend who had a publishing company that published cartoons and that they needed more cartoonists. He said, ‘Your stuff is pretty weird, can you do more?’ So pretty soon my drawings were being published across the country in the underground.

Then I met Rick Griffin, who was like the big poster artist in San Francisco. He had just blown out up there and wanted to retreat back to Southern California and just surf. I had just moved to Santa Monica and I met him down at the pier. I was trying to be cool, but this guy was like God to me. I showed him some of my stuff and he invited me to his studio. I walked in there and he had half-done posters for the Beatles and everyone, it was transformational. Pure enlightenment. He decided to take me under his wing and started giving me work. He was swamped and gave me an album cover to design. I had never designed an album cover before, and it was for Alice Coltrane, so he showed me what to do, and I was stressed because I couldn’t work that fast. The deadline was so quick that I couldn’t even think of what to draw, so I just sat down and grabbed a bunch of pieces of paper and whatever I saw, I would draw. That set me off because it was a big job for a big company. Then I got a job as an Art Director for a music festival, and started to do all of the art for the events. One thing led to another and my portfolio just began to grow.

I went to Hawaii for a while because I was fed up with the politics of this country, and needed a more laid back escape. I did concert posters for a lot of the huge headliners that ended up playing shows in Hawaii. The industry was super small, so it was easy to become the largest frog in such a small pond. I mean seriously sometimes I would end up having dinner with huge artists like James Taylor.

What did poster artwork look like at this time?

Everyone was concentrating on Art Nouveau; most of the artists were really concentrating on that turn of the century stuff. In my mind that had gone out of style five years prior so I really concentrated on a more pop culture, really highly designed aesthetic. Things went really well, but everything was taking off on the homeland.

So when you went back to Los Angeles what were you working on?

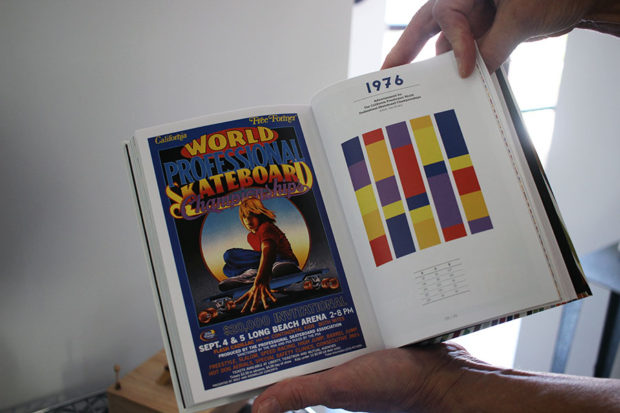

I hit up some agencies that represented artists, and jumped right in. I probably had a decade of just cranking work out; album covers, movie posters, concert posters. A bulk of the stuff that I did for Surfer and Skateboarder Magazine, I did stuff for Playboy, and different men’s magazines. They would pay double truckloads of money for illustrations for a spread about Timothy Leary’s experiences in prison.

As a musician and artist, you were creating and designing work from an insider’s perspective. Do you think that was an advantage in being able to visualize the music for a poster or album cover?

I think so, I’ve always been able to sit with someone and understand. Like I would sit with these stoned musicians and they would describe this elaborate scene and says stuff like, ‘Picture the desert, it’s not just a regular one it’s a psychedelic desert, and I’m walking from far away dragging my guitar, and I want the sky to be Native Americans’ faces, like the cloud formations. The sun will be casting this big shadow on me, and this eagle will be flying over head.” I would sit there and just try to visualize it and get it down on paper. This was pretty much the exact scenario I had with the guitarist from the Doors. I asked him what guitar he wanted to be holding in the picture and he showed it to me and I took some photos of it and him and just started drawing.

So that was your process, just sit there with a musician, have them describe what they wanted, and then you visually project their description on paper?

Yeah, they have a bit of an idea, and then they want more of an idea. A lot of the time the record labels wouldn’t like the musicians’ ideas for the album cover, so they would hire me to do two different ones. One to appease the band, with no intent to publish it, and then another that they could use to sell records.

I feel like if you’re a great artist, you’re not necessarily a fantastic music poster designer? There’s some type of innate skill to designing a great poster.

The ability to do a good poster is really just having the ability to do a good poster. I mean a really good artist can’t do a poster at all. Like one of the things that you have to realize is that the poster needs to be able to be read in a few seconds. To do a good poster, I imagine my poster being on a telephone pole and someone driving past it in a car and being able to read it and get all the pertinent info from it; venue, band, date. That’s where I start from and then build out from there. Sometimes it’s a strong central image, but I never let the image overwhelm the message. But if the image is the message, then all you need is the image. You saw that in the 60s, where you could just print an image and people knew, and the image was really strong. A poster artist understands that people aren’t really different; the way we think, and take in information, what colors appeal to the eyes, etc.

Do you think a poster or an album cover can make or break a show or the sale of an album?

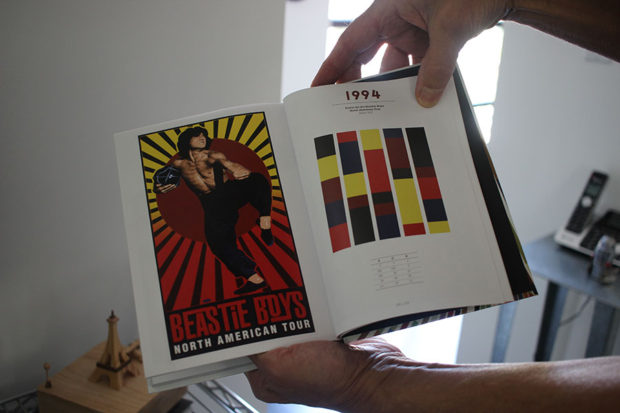

At one time album covers did have that influence, but right now posters are kind of a secondary add-on, they’re not as necessary as they were before because people can go online and look up information about a show or event. Now they just print them for the kids who want to buy them at the show. They don’t serve the same purpose they once did. In the 90s you saw a little resurgence of posters being put up on the streets and in record stores. It’s funny back in the 60s and 70s I didn’t really think twice about what I was doing. I would make the artwork and just give it to the record company. Then when they started making the books in the 80s about all the poster art and my posters were featured, it was crazy to me that people thought they were such important pieces of art and cultural history.

How did TAZ come about?

At the end of the 70s, I was burnt out. I had done so much work and people are always looking for something better than your last piece. I had made some pretty iconic imagery for these bands, but it’s hard to do that over and over again. Also people started tapping me for a specific aesthetic that I became known for, that typical Southern California vibe surrounding skateboarding, surfing, the beach, etc. It became like that feeling a band gets when they play their same radio hit over and over again. Sometimes your biggest hit can set you back. So in the 80s I started doing more fine art.

I was working on something with a gallery in the Valley, and I had just met L7 and they suggested I get back to my rock and roll stuff. I did a poster for L7 and took it back to that gallery and they asked if I could do more. They were super into the silk-screened band posters. I wanted to create something that wasn’t just me. I knew this guy Rolo, who was from Tijuana and had these weird, mixed-culture color schemes in screen-printing. I used to call them “Tijuana taxi colors”. Then my son was working on Desktop Publishing at the time and I realized we could make our own wacky fonts. So I formed TAZ, which is named after this philosophy book called the Temporary Autonomous Zone, and it was just a free form zone, where everyone works his part and then we all put it together for the poster. What makes the TAZ posters so interesting is the fact that it’s not one specific style; it was the collaboration of three different artists creating. My motto was kind of like, “Whatever fucked up color Rolo wants to do, let him do it,” and “Whatever crazy type my son wants to do, let him do it.”

What have been some of TAZ’s most infamous posters over the years?

I went Downtown to go pick up some pictures for Rage Against the Machine, they had a communist bookstore down there and I wanted to get some photos of Angela Davis and the Black Panthers. I walked out of the bookstore and saw this Mexican newspaper stand with the Luchadores magazine hanging there. I picked one up and I flipped through it and was like, “Holy crap!” It was all of this stuff and visuals that no one has used or done before. I did one for the Ramones with a Mexican wrestler on it. I did one for the Beastie Boys – they hired me to do a poster – and I made them all into Mexican wrestlers, and Mike D. just went nuts for it. He wanted Mexican wresters on this, that and the other. And Rolo killed it with the colors for those projects. That was in his wheelhouse.

TAZ and RISK’s collaborative exhibition “Unconventional Forces" at Buckshot Gallery opens Saturday, May 14th, with an opening reception from 7:00PM - 10:00PM.

Words & Interview: Alex Khatchadourian.